Biblical scholar Murray Smith has described the joyful emotions he felt when seeing the only surviving copy of the Didache, an early Christian text, in Jerusalem last week.

“What a blast! What a privilege!” Dr Smith, a biblical studies lecturer at Christ College in Burwood, NSW, wrote afterwards on his Facebook page.

“It’s just really exciting – it puts you in touch with part of our Christian history, part of our Christian heritage,” Dr Smith told Eternity from Jerusalem.

“I’ve been studying the text of the Didache for years and I’ve published a paper on it … I’m used to sitting at my computer looking at an electronic text and it just brings it to life to see the original manuscript with the text on it. It just confirms the authenticity of what you’ve been studying.”

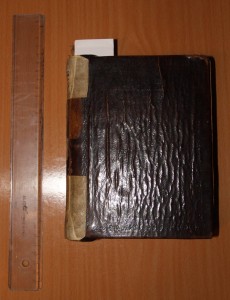

It’s believed that the original Didache, or The Teaching of the Twelve Apostles on church order and leadership, was written in AD110, making it one of the earliest Christian texts outside the New Testament. The surviving copy, called Codex Hierosolymitanus, dates from AD1056 and is housed in the Library of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

“It was such a surprise to see the Didache,” Dr Smith confessed. “Some of my colleagues who are experts in the Didache have never seen it. A couple have seen it but it took months of backwards and forward correspondence. So it really is quite remarkable. I wasn’t expecting to get permission, certainly not so fast.”

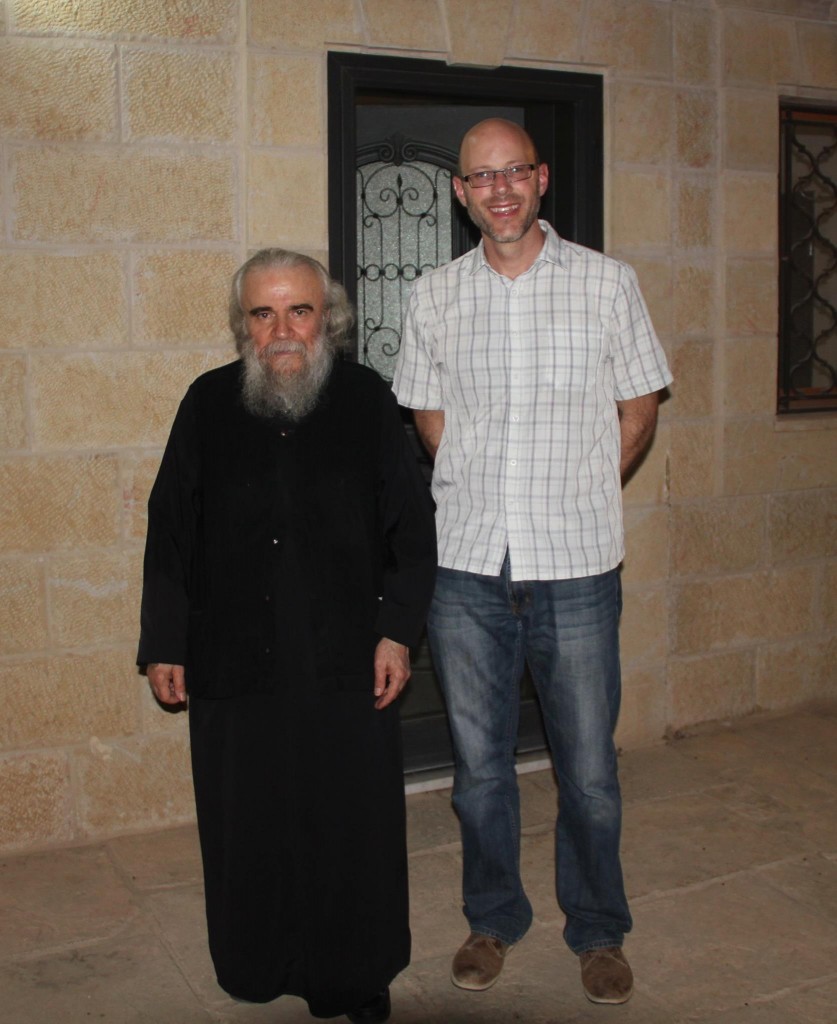

Dr Smith said he had applied unsuccessfully to see the manuscript on an earlier study tour to Jerusalem. This time, he simply knocked on the door of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem and presented a letter from his college to Archbishop Aristarchos, who invited him to a viewing that evening.

“I think I just got the Archbishop on a good day!” he said.

Dr Smith described the tome as 16 chapters long, about the length of the gospel of Mark. Inside are parchment leaves of animal skin, written on in brownish-black ink.

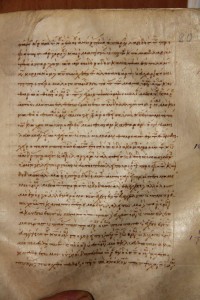

“It’s in quite a nice hand, so it’s pretty to look at, a bit like calligraphy. But if you know Greek it’s very readable.”

Dr Smith said he was able to see things that are not visible in a printed text, such as marginal notes or corrections by the scribe. He was also able to confirm with his own eyes that after the last verse the scribe left a blank space at the bottom of the page.

“That’s really interesting to see because … that seems to imply that the text was broken off and that he is aware that there’s more to it but he didn’t have access to it, so he left space in case somebody else could fill it in later on.”

Dr Smith was excitedly anticipating seeing the Dead Sea Scrolls in a Jerusalem museum earlier this week.

“When you compare the text in the Great Isaiah Scroll from the Dead Sea Scrolls with the manuscripts we had until that point from the 11th century, the text is almost identical – there are just a small number of scribal errors. Which tells you that the transmission of the text is very reliable; the scribe has been very careful that over a 1000-year period the text has remained the same. That gives you great confidence that what we’re reading in Isaiah is actually what Isaiah wrote.”

Dr Smith described the thrill of holding ancient artefacts as partly intellectual in that it put you in touch with other people from very different times and different places, and partly emotional because of the significance of the texts to him as a Christian.

“It gives me a great joy. It matters because I’ve based my life on the claims of these texts, and I try to live in accordance with what they say and I know the gospel through these texts, and that’s at the very heart of who I am and who my family is and who our church community are,” he said.

“Living as a Christian is not an easy thing, in both the struggle to live a faithful Christian life and also in the sense of Christians being maligned or criticised and the Bible being dismissed, false claims being made about it; and so there’s a kind of confirmation and encouragement that what you’ve based your life on is not false, and that gives you confidence to press on.”

Historian, author and founder of the Centre for Public Christianity John Dickson felt like a “kid in a candy shop” when he travelled the world examining ancient documents for the documentary, The Christ Files.

“For a Bible nerd, it feels wonderful to hold our only copy of the Gnostic gospel of Thomas, which is in Coptic, the famous Latin manuscript of the works of Josephus and probably the most precious thing I got to hold was the most ancient copy of Paul’s letters.”

Dr Dickson said he felt overwhelmed when he held a page of the famous P46 manuscript – the oldest copy of Paul’s letters. P46 is kept in climate-controlled vaults the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin. It was brought out on a trolley under heavy security, and Dr Dickson had to wear gloves to handle it.

“I got to hold the oldest manuscript of the oldest

Christian statement,” he said.

“It was no longer in a footnote – it was actually in my hand – so it was a stunning sort of imaginative experience. Here I am, face to face with our closest access to Paul’s own writings, so I wouldn’t class it as spiritual but it is deeply evocative for my imagination.

“I was so overwhelmed when I held that particular page from 1 Corinthians that I turned around to the curator of the museum and I said ‘How much would this be worth?’ That is really not the question to ask and he said ‘We do not discuss such things’ and he said it in a really condescending tone. The reality is that it’s priceless, perhaps the most precious Christian artefact in the world.”

It was also comforting to confirm that every page of P46 that Dr Dickson held says the same as our English text does.

“My Greek is pretty good and I could look at the words and think: ‘Oh my goodness, it does say that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures.’ Even though my NIV might be from the year 2000, I can actually look at a manuscript that we know is 1800 years older and it really does say the same thing, just in a different language.”

For Alanna Nobbs, professor of ancient history at Macquarie University in Sydney, her most exciting encounter with an ancient text was with an early fragment of the Book of Acts, probably from the early 3rd century.

She didn’t realise what it was when she bought it from a papyrus dealer in Vienna, but a research associate, Dr Stuart Pickering, made the connection after noticing that it had a nomen sacrum (divine name) on it.

“I was stunned and amazed,” Professor Nobbs said.

“I can still remember rushing over to have a look at it and to realise this is a fragment of a very ancient book of the Bible was just tremendous.

“We then had it dated and it’s a very early fragment – it may or may not be the earliest. Subsequently we found that there was a much larger fragment from the same Book of Acts, which was in Milan, but it had been bought from the same dealer.

“The fact that we’ve got, in Macquarie University, in our museum, one of the earliest fragments of the Book of Acts is a real thrill to me. The fact that I got it is even more of a thrill.

“It’s exciting to know that somebody handled that piece in antiquity and in a devout manner too.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?