Australia’s first people to get the Bible in more languages, and faster

Changing the process of translating the Bible, which puts Indigenous translators in charge, will mean more language groups will get the Bible more quickly.

Bible translations in major Indigenous languages in Australia are being used as a springboard for further translations into smaller, clan languages. The process has the potential to make more Bible translations available to Australia’s many small indigenous languages. And it’s Indigenous Christians driving the process.

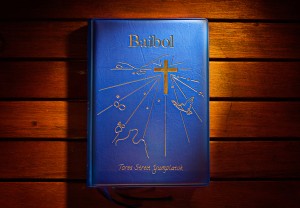

For example, the Yumplatok New Testament was published by Bible Society in 2014 after a painstaking translation process that took 27 years, led by translators Michael and Charlotte Corden from the Australian Society for Indigenous Languages (AuSIL). Yumplatok, also known as Torres Strait Creole, is widely spoken in the Torres Strait as both a first and second language. Some Islanders wanting to do translation into their traditional languages are looking to the Yumplatok translation to lead the way.

The Yumplatok New Testament is one translation being used as a springboard for other Indigenous Bible translations.

Director of AuSIL, Dr Barbara Grimes says the approach to Bible translation is undergoing a “massive shift” as organisations like AuSIL and Bible Society seek to maximise the ownership and involvement of Indigenous people in the Bible translation process.

“We feel that we need to put the task [of Bible translation] as much as possible into the hands of Indigenous people,” said Dr Grimes. “The Yumplatok New Testament translation has made this process possible in the Torres Strait. Indigenous people often speak several languages, and as more major language translations become available, it opens the possibility for them to use the major language translation to draft into their own languages too.”

Bible Society translation consultant Paul Eckert, who has been working on a translation of the Pitjantjatjara Bible for over 20 years in the APY Lands in remote northwest South Australia, says translating the Bible from major language translations into other traditional languages has the potential to be a faster translation process, cutting out what can be several years of language learning for a non-Indigenous translator.

Historically, Bible translators and linguists would spend many years learning the Indigenous language before the translation process could begin. Like the Yumplatok Bible, 30 years is not an unusual length of time for Indigenous Bible translations. In the Pitjantjatjara language, translating the Old Testament to complete the full Bible is expected to take another 10 years.

“I started translating after I’d been learning the language for about five years, and I had a very good situation in which to learn Pitjantjatjara … a couple of years where I was embedded in a situation where I was speaking it most of the time and that was very helpful. But that’s not always the case. And even then, I look back on some of that early translation work and think, ‘Oh boy, I don’t know what I was thinking then.’ There’s a lot to learn about the nuances in language usage. It takes time,” says Paul.

In East Arnhem Land where there are many Yolŋu languages, the same process is being used. The Djambarrpuyŋu New Testament translation published in 2008 is now being used for translation into other Yolŋu languages. They are making exciting progress.

“People in North East Arnhem Land understand Djambarrpuyŋu much more easily than English, so Yolŋu translators are using the published Djambarrpuyŋu New Testament as a ‘front translation’ for drafting Scripture into other Yolŋu clan languages,” wrote translators Dr Marilyn McLennan and Hannah Harper on the Uniting Church’s Coordinate blog for Indigenous Scripture projects in 2013, when translation was beginning.

“The mother tongue translator already knows both languages well, so it cuts out the language learning side of things, which can be quite a few years in the process,” says Paul. “But they still need to be trained to be Bible translators, to produce a good, clear, natural translation.”

Barbara from AuSIL says that the new process of using Indigenous language front translations by which to translate into other languages is not about making things faster – though from a long-term perspective this may well be the case.

“In the long term, we hope that there will be more translations done because of this method, she says. “New linguists joining AuSIL will be expected to work on not just one language but 3 or 5 or 7 languages because they’ll be acting as facilitators with Indigenous teams doing much of the translating themselves. So their capacity goes from one language per linguist over, say, 30 years, to five to seven languages over that same time period.”

“But this isn’t about speed. It will still be a slow process. It will still require the involvement of trained linguists and Bible translators, to ensure a quality product. But if Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people are passionate [about Bible translation], they can now be actively involved from the beginning, using our programs.

“It’s about maximising the ownership and contribution of Indigenous people. They can be much more involved and take the initiative in getting the translation process started. They don’t have to be translating at the side of a trained linguist – the Indigenous person is the one who knows the language best. They can draft translation on their own, sitting on their porch or out under a tree.”

Email This Story

Why not send this to a friend?